Generalized Expectation Maximization [1]

This technical report describes the statistical method of expectation maximization (EM) for parameter estimation. Several of 1D, 2D, 3D and n-D examples are presented in this document. Applications of the EM method are also demonstrated in the case of mixture modeling using interactive Java applets in 1D (e.g., curve fitting), 2D (e.g., point clustering and classification) and 3D (e.g., brain tissue classification).

Table

of Contents

1

Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE)

2

General Expectation Maximization (GEM) Algorithms

Application

1 (Missing Values)

Application

2 (Pattern Recognition)

3 EM

Application: Finding Maximum Likelihood Mixture Densities Parameters via EM

Example

3: 1D Distribution Mixture-Model-Fitting using EM

Example

4: 2D Point Clustering and Classification using EM

Example

5: 3D Brain Tissue Classification using EM and Mixture Modeling

1 Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE)

First, let’s

recall the definition of the maximum-likelihood estimation problem. We have a

density function p

(x | Q), that is governed by the set of parameters Q (e.g.,

p might be a Gaussian and Q could be the means (vector) and covariance

(matrix)). We also have a data set of size N, supposedly drawn

from this distribution with density p, i.e., X = {x1,

…, xN}. That is, we assume that these data vectors are

independent and identically distributed (IID) with distribution p . Therefore, the resulting joint density for

the samples is:

![]() is called the likelihood

function of the parameters (Q)

given the data, or just the likelihood. The likelihood is thought of as a

function of the parameters (Q) where

the data X is fixed (observed). In the maximum likelihood problem, our goal is to

find a parameter vector Q that

maximizes

is called the likelihood

function of the parameters (Q)

given the data, or just the likelihood. The likelihood is thought of as a

function of the parameters (Q) where

the data X is fixed (observed). In the maximum likelihood problem, our goal is to

find a parameter vector Q that

maximizes ![]() . In other words, we

look for Q*

, where

. In other words, we

look for Q*

, where

![]()

Oftentimes we

choose to maximize ![]() instead because it is analytically easier or

computationally appealing.

instead because it is analytically easier or

computationally appealing.

Depending on the

form of p (x | Q)

this problem can be easy or hard. For example, if p (x | Q)

is simply a single Gaussian distribution where the parameter vector Q=(m, s2),

then we can solve the

maximum likelihood problem of determining estimates (MLE) of m & s2

by setting the partial derivatives of ![]() to zero (in fact, this

is how the familiar formulas for the population mean and variance are obtained). For many problems, however, it is not

possible to find such analytical expressions, and we must resort to more

elaborate techniques (e.g., EM technique).

to zero (in fact, this

is how the familiar formulas for the population mean and variance are obtained). For many problems, however, it is not

possible to find such analytical expressions, and we must resort to more

elaborate techniques (e.g., EM technique).

Example 1: Nornal(m,s2)

Suppose {X1, …, Xn} IID N(m, s2),

where m is

unknown. We estimate m by: ![]() .

.

Example 2: Poisson(l)

Suppose {X1, …, XN} IID Poisson(l),

where (the population mean, and standard deviation) l is

unknown. Estimate l by:

![]()

2 General Expectation Maximization (GEM) Algorithms

The EM algorithm

is one such technique, which allows estimating parameter vectors in the cases

when such analytic solutions to the likelihood minimization are difficult or

impossible. The EM algorithm [see references at the end] is a general

method of finding the maximum-likelihood estimates of the parameters of an

underlying distribution from a given data set when the data is incomplete or has

missing values. There are two main applications of the EM algorithm.

Application 1 (Missing Values)

The first application of EM algorithm occurs when the data indeed has missing values, due to problems with or limitations of the observation process.

Application 2 (Pattern Recognition)

The second occurs

when optimizing the likelihood function is analytically intractable, however,

we still need to assume the likelihood function can be simplified by assuming

the existence of and values for additional but missing (or hidden)

parameters. This second application is more common in the computational pattern

recognition community.

As before, we

assume that data X is observed and is generated by some

distribution. We call X the incomplete

data. We assume that a complete data set exists Z=(X;Y) and also assume (or specify) a joint density

function:

![]()

Recall that for each probability measure, P, P(A,B)=P(A|B)P(B)

and hence, in terms of the conditional probability, P(A,B|C) =

P(A|B,C)P(B|C). This joint density often times arises from the marginal

density function ![]() and the assumption of

hidden variables and parameter value guesses (e.g., mixture-densities, this

example is coming up; and Baum-Welch algorithm). In other cases (e.g., missing

data values in samples of a distribution), we must assume a joint relationship

between the missing and observed values.

and the assumption of

hidden variables and parameter value guesses (e.g., mixture-densities, this

example is coming up; and Baum-Welch algorithm). In other cases (e.g., missing

data values in samples of a distribution), we must assume a joint relationship

between the missing and observed values.

With this new

density function, we can define a new likelihood function,

![]() ,

,

called the complete-data likelihood. Note that this

function is in fact a random variable since the missing information Y

is unknown, i.e., random, and presumably governed by an underlying

distribution. That is, we can think of ![]() for some function

for some function ![]() , where X and Q are constant

and Y is a random variable.

The original likelihood

, where X and Q are constant

and Y is a random variable.

The original likelihood ![]() is referred to as the incomplete-data likelihood function.

is referred to as the incomplete-data likelihood function.

The Expectation

Maximization algorithm then proceeds in two steps – expectation followed by its

maximization.

Step 1 of EM (Expectation)

The EM algorithm

needs to first find the expected value of the complete-data log-likelihood ![]() with respect to the unknown data Y given the observed data X and the current parameter estimates Qi, the E-Step. Below we define

the expectation of Q(i-1), the second argument represents the

parameters that we use to evaluate the expectation. The first argument Q simply indicates the parameter (vector) that

ultimately will be optimized in an attempt to maximize the likelihood:

with respect to the unknown data Y given the observed data X and the current parameter estimates Qi, the E-Step. Below we define

the expectation of Q(i-1), the second argument represents the

parameters that we use to evaluate the expectation. The first argument Q simply indicates the parameter (vector) that

ultimately will be optimized in an attempt to maximize the likelihood:

Q(Q, Q(i-1))=E[Log p (X,Y | Q) | X, Q(i-1)]. (1)

Where Q(i-1) are the current parameters estimates that we

used to evaluate the expectation and Q are

the new parameters that we optimize to increase (maximize) Q. Note that the expression above is a conditional

expectation w.r.t. (X & Q(i-1)),

i.e.,

E[ h(Y) |

X=x] :=![]() .

.

The key thing to

understand is that X and Q(i-1) are given constants, Q is a random variable that we wish to

adjust/estimate, and Y is a

random variable governed by the distribution f(Y |X,Q(i-1)). The right side of

equation (1) can therefore be expressed as:

![]() (2)

(2)

The f(Y |X,Q(i-1)) is the marginal

distribution of the unobserved data (Y) and is dependent on: the

observed data X, on the

current parameters Q(i-1), and Y is the space of values y can

take on. In the best-case situations, this marginal distribution is a

simple analytical expression of the assumed parameters Q(i-1), and perhaps

the observed data (X). In the worst-case scenario, this

density might be very hard to obtain. In fact, sometimes the actually used

density is:

f(y

,X | Q(i-1))= f(y | X,Q(i-1)) f(X | Q(i-1)),

but this doesn’t

effect subsequent steps since the extra factor, f(X | Q(i-1)) is not

dependent on Q.

As an analogy,

suppose we have a function h( . ; . ) of two variables. Consider h( q ; Y ) where q is a

constant and Y is a random

variable governed by some distribution fY(y). Then

![]()

is now a

deterministic function that could be maximized if desired, w.r.t. q. The evaluation of this expectation is

called the E-step of the

algorithm. Notice the meaning of the two arguments in the function Q(Q, Q(i-1)). The first argument Q corresponds

to the parameters that ultimately will be optimized in an attempt to maximize

the likelihood. The second argument, Q(i-1), corresponds to the parameters that we use

to evaluate the expectation at each iteration (EàM à EàM à EàM à …).

Step 2 of EM (Maximization)

The second step

(the M-step) of the EM algorithm is to maximize the expectation

we computed in the first step. That is, we iteratively compute:

That is we maximize the expectation of the log-likelihood function. These two steps are repeated as necessary. Each iteration is guaranteed to increase the log-likelihood and the algorithm is guaranteed to converge to a local maximum of the likelihood function. There are many theoretical and empirical rate-of-convergence papers (see references below).

A modified form of

the M-step is to, instead of maximizing the rather difficult function Q(Q, Q(i-1)), we find some Q(i) such that Q(Q(i), Q(i-1)) > Q(Q, Q(i-1)). This form of the algorithm is called

Generalized EM (GEM) and is also guaranteed to converge. This

description of the GEM does not yield a direct computer implementation scheme

(it’s not constructive (the coding algorithm is not explicit). This is the way,

however, that the algorithm is presented in its most general form. The details

of the steps required to compute the given quantities are very dependent on the

particular application, so they are not discussed when the algorithm is

presented in this abstract form, but rather detailed for each specific

application.

3 EM Application: Finding Maximum Likelihood Mixture Densities Parameters via EM

The

mixture-density parameter estimation problem is probably one of the most widely

used applications of the EM algorithm in the computational pattern recognition

community. In this case, we assume the following (mixture-density) model:

![]()

where the

parameter vector is Q=(a1, …, aM ; q1, …, qM), where the mixture-model weights satisfy ![]() and each pi is

a density function parameterized, in general, by its own parameter vector qi. In other words, we assume we have M component

densities mixed together with M mixing coefficients ai .

and each pi is

a density function parameterized, in general, by its own parameter vector qi. In other words, we assume we have M component

densities mixed together with M mixing coefficients ai .

The

incomplete-data log-likelihood expression for this density from the data X={x1,

…, xN}, N = # Observations,

is given by:

![]()

which is difficult

to optimize because it contains the logarithm function of the sum [if the sum

and the log were interchanged then optimizing the outside logarithm would have

been equivalent to optimizing its argument – the sum – as the log function has

always a positive derivative over its domain (0; ![]() )]. If we consider X as incomplete, however, and

assume the existence of unobserved data items Y={yi}i=1N, whose values inform us which component

density “generated” each data item, the likelihood expression is significantly

simplified. That is, if we assume that

)]. If we consider X as incomplete, however, and

assume the existence of unobserved data items Y={yi}i=1N, whose values inform us which component

density “generated” each data item, the likelihood expression is significantly

simplified. That is, if we assume that ![]() for each

for each ![]() , and yi=k if the ith

sample, xi, was generated by the kth mixture component pk. If we

know the values of Y, the likelihood becomes:

, and yi=k if the ith

sample, xi, was generated by the kth mixture component pk. If we

know the values of Y, the likelihood becomes:

![]()

which, given a

particular form of the component densities, can be optimized using a variety of

techniques. The problem, of course, is that we do not know the values of Y.

If we assume Y is a random

vector, however, we can proceed. We first must derive an expression for the

distribution of the unobserved (missing) data, Y. Let’s first

guess at parameters for the mixture density, i.e., we guess that Qg =(a1g,

…, aMg

; q1g, …, qMg), are the

appropriate parameters for the likelihood L(Qg | X,Y). Given Qg, we can compute pj(xi|qjg) for each i

and j. In addition, the mixing parameters, ai, can

be though of as prior probabilities of each mixture component, that is ai= p(component i). Therefore, using Bayes’s rule – P(Yi|Xi)=P(Xi|Yi)P(Yi)/P(Xi),

we can compute:

and therefore, ![]() , where y = (y1,

…, yN)

is an instance of the unobserved

data independently drawn. When we now look at equation (2), we see that in this

case we have obtained the desired marginal density (of Y), f(y

| X,Q(i-1)), by assuming the existence of the hidden variables and making a guess

at the initial parameters of their distribution. In this case, equation (1)

takes the specific form:

, where y = (y1,

…, yN)

is an instance of the unobserved

data independently drawn. When we now look at equation (2), we see that in this

case we have obtained the desired marginal density (of Y), f(y

| X,Q(i-1)), by assuming the existence of the hidden variables and making a guess

at the initial parameters of their distribution. In this case, equation (1)

takes the specific form:

where  . In this form,

. In this form, ![]() appears computationally challenging, however,

it can be simplified, since for

appears computationally challenging, however,

it can be simplified, since for ![]() ,

,

This is because ![]() . Using equation (5), we can write equation (4) as:

. Using equation (5), we can write equation (4) as:

Now, to maximize

this expression, we can maximize independently F and

Y, the terms containing al and ql, since

they are not related. To find the expression for al, which maximizes Q(Q,Q(g)), we introduce the Lagrange multiplier l with the constraint that ![]() , and solve

the following equation:

, and solve

the following equation:

This yields:

Summing over l we get:

Therefore, l = -N , which yields that  . This is how we determine the mixture parameters {al}, most of the time.

. This is how we determine the mixture parameters {al}, most of the time.

Now let us try to estimate the second part of the

parameter vector Q=(a1,

…, aM ; q1, …, qM), i.e., the distribution specific parameters (q1, …, qM). Clearly, these need to be estimated in a case by case manner, as

different distributions have different number and type of parameters. We

consider again a couple of cases that illustrate the basic strategy for

estimating (q1, …, qM) using EM approaches. For some distributions, it will be possible to

get analytic expressions for ql directly, as functions of all other

variables.

4. Examples

Example 1: Poisson(l)

Suppose that the mixture model in equation (3) involves

Poisson(ll)

distributions, ![]() . Then the

. Then the

Taking the

derivatives w.r.t. ll and setting these equal to zero yields,

Therefore, we have explicit expressions for

iterative calculation of the estimates of the mixture parameters, Q=(a1, …, aM), and the Poisson distribution parameters, (q1, …, qM)=(l1, …, lM).

Example 2: n-D Gaussian

If we assume d-dimensional

Gaussian component distributions with a mean vector m and covariance matrix S, i.e., q = (m; S) then the

probability density function is

![]()

Then we may derive

the update equations [equations (1), (4), (6)] for this specific distribution,

we need to recall some results from matrix algebra. The trace of a

square matrix tr(A) is

equal to the sum of A’s diagonal elements. In 1D the trace of a

scalar equals that scalar. Also, tr(A + B) = tr(A) + tr(B), and tr(AB) = tr(BA), which

implies that ![]() . Also note that |A| indicates the determinant of the

matrix A, and |A-1|=1/|A|. Differentiation of a

function of a matrix f(A) is accomplished by differentiating with respect to elements of

that matrix. Therefore, we define df(A)/dA to be the matrix with

(i,j)-th entry equal to [df(A)/dai,j], where A=( ai,j).

This definition also applies taking derivatives with respect to a vector.

First, d(xTAx)/dx=(A+AT)x. Second, it can be shown

that when A is a symmetric matrix:

. Also note that |A| indicates the determinant of the

matrix A, and |A-1|=1/|A|. Differentiation of a

function of a matrix f(A) is accomplished by differentiating with respect to elements of

that matrix. Therefore, we define df(A)/dA to be the matrix with

(i,j)-th entry equal to [df(A)/dai,j], where A=( ai,j).

This definition also applies taking derivatives with respect to a vector.

First, d(xTAx)/dx=(A+AT)x. Second, it can be shown

that when A is a symmetric matrix:

where Ai,j

is the (i,j)-the cofactor of A. Given the above, we see that:

by the definition

of the inverse of a matrix. Finally, it can be shown that dtr(AB)/dA

= B + BT-diag(B).

Now, for the d-dimensional

Gaussian distribution example, if we take a log of equation (7), ignoring any

constant terms (since they disappear after taking derivatives), and

substituting into the right side of equation (6), we get:

Taking the

derivative of equation (8) with respect to ml and setting it equal to zero, we get:

which solving for ml yields:

To find Sl, note that we can write equation (8) as:

where Nl,i = ![]() . In equation (9)

we now take the derivative with respect to the matrix Sl-1, and we obtain:

. In equation (9)

we now take the derivative with respect to the matrix Sl-1, and we obtain:

where Nl,i = ![]() , Ml,i =

Sl – Nl,i and S =

, Ml,i =

Sl – Nl,i and S =  . To find the extreme

values (maxima) of the , equation (9) we set the derivative to zero [equation

(10)], i.e., 2S – diag(S) = 0. This implies that S=0 è

. To find the extreme

values (maxima) of the , equation (9) we set the derivative to zero [equation

(10)], i.e., 2S – diag(S) = 0. This implies that S=0 è ![]() So, we obtain an exact

expression (variance-covariance matrix estimate, 1

So, we obtain an exact

expression (variance-covariance matrix estimate, 1 ![]() l

l ![]() M) for Sl.

M) for Sl.

Summarizing, the

estimates of the new parameters in terms of the old parameters (guessed

parameters super-indexed by g, Qg =(a1g, …, aMg ; q1g, …, qMg)) are as follows:

Note that the above equations

(11) perform both the expectation step and the maximization step

simultaneously. The algorithm proceeds by using the newly derived parameters as

the guess for the next iteration.

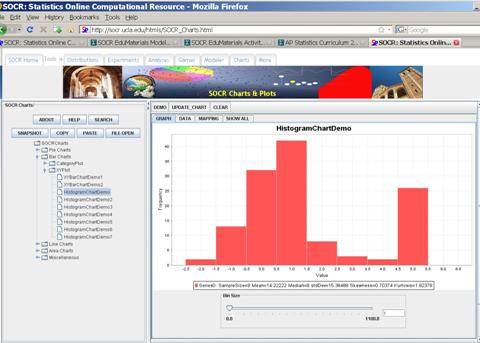

Example 3: 1D Distribution Mixture-Model-Fitting using EM

These SOCR Activities demonstrate fitting a number of polynomial,

distribution and spectral models to data: http://wiki.stat.ucla.edu/socr/index.php/SOCR_EduMaterials_ModelerActivities.

For instance, suppose we have a collection of 100 observations. The

first 20 of these observations are included in the table below. A histogram of

these observations is also shown below.

|

1 |

-2.51002 |

|

2 |

-2.51002 |

|

3 |

-1.5060121 |

|

4 |

-1.5060121 |

|

5 |

-1.5060121 |

|

6 |

-1.5060121 |

|

7 |

-1.5060121 |

|

8 |

-1.5060121 |

|

9 |

-1.5060121 |

|

10 |

-1.5060121 |

|

11 |

-1.5060121 |

|

12 |

-1.5060121 |

|

13 |

-1.5060121 |

|

14 |

-1.5060121 |

|

15 |

-1.5060121 |

|

16 |

-0.502004 |

|

17 |

-0.502004 |

|

18 |

-0.502004 |

|

19 |

-0.502004 |

|

20 |

-0.502004 |

These data was generated using SOCR Modeler:

http://socr.ucla.edu/htmls/SOCR_Modeler.html

http://wiki.stat.ucla.edu/socr/index.php/SOCR_EduMaterials_Activities_RNG

And the Histogram was obtained using SOCR Charts:

http://socr.ucla.edu/htmls/SOCR_Charts.html

http://wiki.stat.ucla.edu/socr/index.php/SOCR_EduMaterials_Activities_Histogram_Graphs

If these 100 random observations are copy-pasted in SOCR Modeler (http://socr.ucla.edu/htmls/SOCR_Modeler.html), we can fit in a mixture of 2-Normal Distributions to these data, as shown in the figure below. The quantitative results of this Em fit of 2 Normal distributions to these data is reported in the Results panel.

Mixture Model 0: Weight =0.796875 Mean =

0.06890251005397123 Variance =

1.1959966055736866 Mixture Model 1: Weight =0.203125 Mean = 4.518035888671875 Variance = 1.0 INTERSECTION

POINT(S): 2.708939236914807

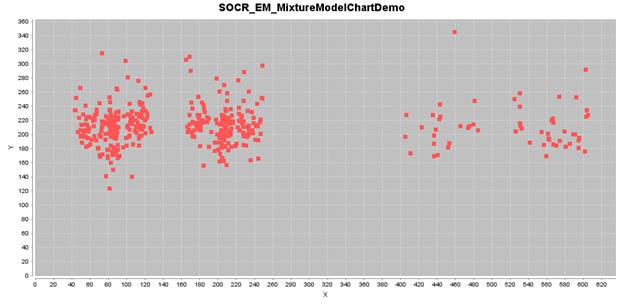

Example 4: 2D Point Clustering and Classification using EM

We can use the SOCR EM Chart, to enter real 2D data or simulate such

data. The figure below shows the plot of knee pain data (courtesy of Colin

Taylor, MD, TMT Medical).

·

http://socr.ucla.edu/htmls/SOCR_Charts.html

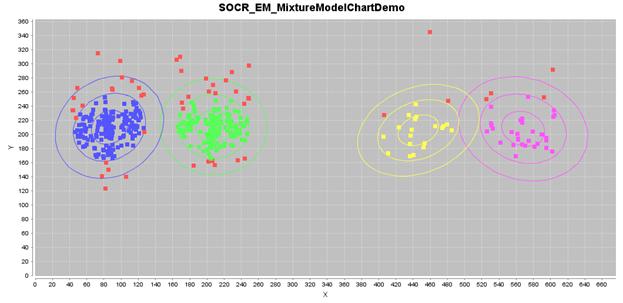

If we select four 2D Gaussian kernels, we can run iteratively the EM

mixture-modeling algorithm to estimate the 4-clusters and finally classify the

points in this knee-pain dataset, as shown in the figure below.

The estimated 2D Gaussian kernels are reported in the table below.

|

Kernel:1 |

Color[r=85,g=85,b=255] |

|

mX = 12.109004237402402 |

mY = 117.82567907801044 |

|

sXX = 21.032925241685124 |

sXY = 78.7581941291246 |

|

sYX = 78.7581941291246 |

sYY = 24.09825818460926 |

|

weight = 0.430083268505667 |

likelihood = -10.208282817360221 |

|

Kernel:2 |

Color[r=85,g=255,b=85] |

|

mX = 149.38436424342427 |

mY = 192.71749953677403 |

|

sXX = 20.76028543262703 |

sXY = -8.73565367620904 |

|

sYX = -8.73565367620904 |

sYY = 22.72742021102665 |

|

weight = 0.39741243015152933 |

likelihood = -10.208282817360221 |

|

Kernel:3 |

Color[r=255,g=255,b=85] |

|

mX = 384.0858049258344 |

mY = 130.33122378944105 |

|

sXX = 23.636423858007923 |

sXY = 135.0559608391195 |

|

sYX = 135.0559608391195 |

sYY = 21.654643444147702 |

|

weight = 0.06547362085865455 |

likelihood = -10.208282817360221 |

|

Kernel:4 |

Color[r=255,g=85,b=255] |

|

mX = 384.0858049258344 |

mY = 147.83898638544392 |

|

sXX = 25.080070954205347 |

sXY = -94.47319742216496 |

|

sYX = -94.47319742216496 |

sYY = 24.591327584325068 |

|

weight = 0.09143983449841454 |

likelihood = -10.208282817360221 |

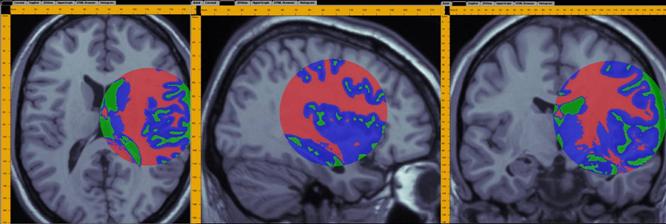

Example 5: 3D Brain Tissue Classification using EM and Mixture Modeling

A demonstration of a 3D data analysis using the SOCR EM Mixture model is included in the LONI Viz Manual (http://www.loni.ucla.edu/download/LOVE/LOVE_User_Guide.pdf). This example shows how 3D brain imaging data may be segmented into three tissue types (White Matter, Gray Matter and Cerebra-spinal Fluid). This is achieved by LONI Viz (Dinov et al., 2006) sending the segmentation tasks to SOCR and SOCR returning back the 3D segmented volumes, which are superimposed dynamically on top of the initial anatomical brain imaging data in real time. The figure below illustrates this functionality. Other external computational tools could also invoke SOCR statistical computing resources directly by using the SOCR JAR binaries (http://www.socr.ucla.edu/htmls/SOCR_Download.html) and the SOCR Documentation (http://www.socr.ucla.edu/docs).

5. Online SOCR Demos

·

http://wiki.stat.ucla.edu/socr/index.php/AP_Statistics_Curriculum_2007_Estim_MOM_MLE

·

http://wiki.stat.ucla.edu/socr/index.php/SOCR_EduMaterials_ModelerActivities

·

http://socr.ucla.edu/htmls/SOCR_Modeler.html

·

http://wiki.stat.ucla.edu/socr/index.php/SOCR_EduMaterials_ModelerActivities_MixtureModel_1

6. References:

A.P.Dempster, N.M.

Laird, and D.B. Rubin. Maximum-likelihood from incomplete data via the EM

algorithm. J. Royal Statist. Soc. Ser. B., 39, 1977.

C. Bishop. Neural

Networks for Pattern Recognition. Clarendon Press,

J.A. Bilmes. A

Gentle Tutorial of the EM Algorithm and its Application to Parameter Estimation

for Gaussian Mixture and Hidden Markov Models. Department of Electrical

Engineering and Computer Science, U.C. Berkeley,

Dinov ID, Valentino D, Shin BC, Konstantinidis F, Hu G, MacKenzie-Graham A, Lee EF, Shattuck DW, Ma J, Schwartz C and Toga AW. LONI Visualization Environment, Journal of Digital Imaging. Vol. 19, No. 2, 148-158, June 2006.

Z. Ghahramami and

M. Jordan. Learning from incomplete data. Technical Report AI Lab Memo No.

1509, CBCL Paper No. 108, MIT AI Lab, August 1995.

M. Jordan and R.

Jacobs. Hierarchical mixtures of experts and the EM algorithm. Neural

Computation, 6:181–214, 1994.

M. Jordon and L.

Xu. Convergence results for the EM approach to mixtures of experts

architectures. Neural Networks, 8:1409–1431, 1996.

L. Rabiner and

B.-H. Juang. Fundamentals of Speech Recognition. Prentice Hall Signal

Processing Series, 1993.

R. Redner and H.

Walker. Mixture densities, maximum likelihood and the EM algorithm.

C.F.J. Wu. On the

convergence properties of the EM algorithm. The Annals of Statistics,

11(1):95–103, 1983.

L. Xu and M.I.

Jordan. On convergence properties of the EM algorithm for Gaussian mixtures. Neural

Computation, 8:129–151, 1996.